Niles native reflects on nine months as traveling nurse taking care of COVID-infected patients all over U.S.

Published 12:35 pm Thursday, March 4, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In Cincinnati, Ohio, hours from her home in Michigan, a nurse stands by a bedside, her iPhone in one hand, her patient’s hand in the other.

The man in her care, a pastor from Ohio, is minutes away from taking his last breath. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, there are no family members in the room. The usual sounds of “I love yous” and stifled tears from loved ones are replaced by beeps and buzzes of medical equipment, the room empty save for a nurse and her patient. The nurse pulls out her phone, turns on gospel music, and prays with the pastor.

With the knowledge that this man would soon succumb to the virus that has killed more than 400,000 Americans since March 2020, the nurse does all she can to make this man — a stranger — comfortable. Knowing her presence is not the same as a loved one’s, she FaceTimes the patient’s daughter, giving them both a chance to say goodbye.

Before she hangs up, Andrea Wright, BSN-RN, promises the daughter she will not leave the pastor’s side, and she keeps her word. In the last nine months, she has witnessed countless COVID-19 patients take their last breaths, but as she says, it never gets easier.

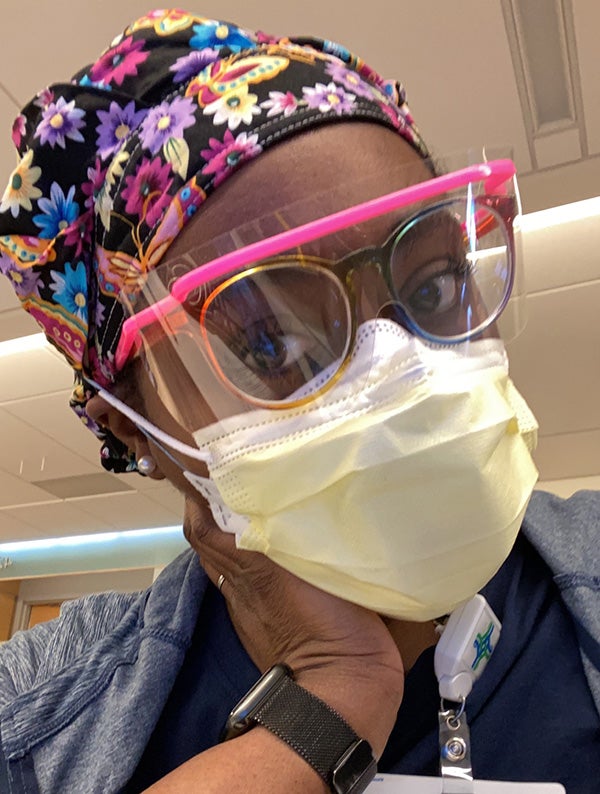

Through two masks, a face shield, a gown and gloves, the travel nurse from Niles sits by her patient’s side and weeps.

On Feb. 28, 1999, a conference room at Riley’s Children’s Hospital in Indianapolis was set up for a birthday party. Instead of the bowling shoes, roller skates or video games that typically accompanied 8-year-olds’ birthdays in the late ‘90s, Wright was treated to a chocolate cake and wrapped presents — an experience that would impact the rest of her life.

A few weeks before her 30th birthday, Wright recalled the special birthday party she celebrated more than two decades ago when her sister was admitted in the hospital. Though her classmates and extended family could not be there, she was surrounded by new friends.

“That was the reason I chose to become a nurse,” Wright said. “They cared enough about this little girl who was not even sick, and not in the hospital — my sister was! They went that extra step to show that compassion.”

For the last several years, Wright has dedicated herself to providing the same level of care to patients and their loved ones all over the country.

In early February, Wright reflected on nearly a decade of nursing as she traveled from her latest assignment in Cincinnati to North Carolina to retrieve personal items from an earlier stint in the year.

Upon graduating from Western Michigan University with a bachelor of science in nursing and a focus on community health, Wright accepted a position as a community health nurse with St. Joseph Health System — a difficult position, but it paled in comparison to the past nine months of work as a traveling nurse on COVID-19 floors across the country.

“[Community health] was hard — very hard because you’re in the homeless shelter. I would do home visits with a social worker, plan community health events on certain diseases and things that are very preventable in public health,” Wright recalled of her first job out of college. “Of course, I was working in underserved populations and with how their healthcare is different across all skin colors, all those things — if you don’t have the access to health care, you’re not going to be successful in your health.”

Eager to grow her career and experience quickly, she accepted an opportunity as a traveling nurse in 2018 that would send her to a new hospital every four to 13 weeks. Since the beginning of the pandemic, she has worked in Washington, D.C., Phoenix, Arizona, Durham, North Carolina, Indianapolis, Cincinnati and Greenville, North Carolina.

“It has been eye opening just to see as a nurse how different our scope can be depending on what state you go to,” she said. “It helps you to have a well-rounded experience as a nurse.”

Each state takes different approaches to medicine in terms of treatment, prescriptions, insurance, accessibility and more.

“[Traveling] definitely has changed my perspective and made me a better nurse and a better person, honestly,” she said.

On a typical pre-pandemic day, a swarm of hospital employees in scrubs of various hues, name badges and white sneakers buzz through the halls, creating a cacophony of footsteps, chatter and squeaking wheels. A seemingly choreographed routine of moving beds, shifting wheelchairs and bustling employees fills the halls.

Some transport patients from their rooms to various tests and therapies. Others push carts filled with food from room to room, delivering meals and offering nutrition advice. Even more transport medicine, draw blood, clean rooms and wash linens.

“We are everything now,” Wright said of the current state of COVID floors at hospitals all over the country. “We are nurses, but we are phlebotomists now. We are respiratory therapists. We are the eyes and the hands and everything.”

Typically, nurses are responsible for directly caring for patients and serving as the liaison between patients and their physicians. Other employees are usually responsible for various tasks like food delivery, sanitation and lab work.

“Depending on what hospital you go to, the physicians don’t even go into [COVID-19] rooms,” Wright said. “They will call the patient if they are able to talk to the patient through the window or the door, or we [nurses] will have to go in the room and bring an iPad in there for the patient so the doctor can communicate.”

In order to minimize the amount of spread from COVID-positive patients to other people, nurses have taken on the brunt of the workload, in many cases serving as the only person patients interact with throughout their stays at the hospital.

“The stress and the burnout that people don’t realize is that in nursing, yes, we already do a lot, and then COVID happened and now these subspecialties cannot for their safety go into those rooms,” she said. “Normally, before COVID, dietary would bring the food into the room for the patient and all those things. Nope, we do all that now, too. Environmental, as far as making sure the rooms are clean and all those things … we do that, too. We are transport. If my patient has to go down for an MRI, we have to take them. … If I have three patients that day and I have to leave the floor with one for a test, I’m off the unit for an hour.”

The biggest challenge, Wright said, has been the high death toll of patients once they are admitted to hospitals with the novel coronavirus that first swept the globe in late 2019.

Recalling the pastor’s death in Cincinnati, Wright solemnly admitted the incident was only the latest of many similar circumstances.

“It’s not just one patient,” she said. “It’s happened almost every other day. … That’s the hardest part of this.”

Like so many nurses across the world, Wright said she has been pushed to limits she did not know she had, but has persevered with support from family and fellow nurses she has met through her travels.

With a bubbly laugh, she said she recently warned her father she was quitting and getting a job at Chick-fil-A.

“That way when something goes wrong, all I have to do is say, ‘my pleasure!’ and smile,” Wright said. “I joke, but it’s definitely crossed my mind a few times.”

Regardless of the toll the job has taken in the past year, Wright feels blessed to have been given the opportunity to care for patients.

“It’s sucked. I’m not going to sugar coat it,” she said. “But I wouldn’t change it. There are bad days all the time, but sometimes you have good days that make those bad days not so bad.”

Take, for example, a patient who was put on a ventilator with little hope of recovering from the virus, days later heading home with plans for respiratory therapy.

“That makes it worth it,” she said.

As she began a month-long vacation between assignments, Wright asked the general public to remain vigilant in mitigation efforts despite lowering COVID-19 case numbers and vaccinations rolling out.

Wright said she and her fellow nurses have been insulted time and time again as acquaintances insist coronavirus has been exaggerated or made up by media outlets. She encouraged those challenging information about the virus to question healthcare experts they trust.

“The best thing you can do is educate yourself, and not educating yourself by your social media research,” she said. “Go talk to your family physician. … Talk to someone who works in the hospital.”

Throughout the last nine months, she said she had met countless people who thought the virus was a hoax, or overplayed by the press, and then contracted it and had a change of heart. The virus, which spreads primarily through respiratory droplets during human contact, has been known to spread wildly at events and gatherings where masks are not worn and social distancing is not observed.

“I don’t care if you live your best life and go on a trip, just wear a mask,” Wright said. “And don’t go around sick family members.”

With many months of caring for patients sick with COVID ahead, Wright pleaded with anyone questioning the severity of the coronavirus to do their part, if not for themselves, for people around them.

“It’s a slap in the face to our profession, for one,” she said. “If you’d like to come and trade places with me, I dare you.”