Dowagiac 175: The Frontier Era

Published 9:34 am Friday, March 17, 2023

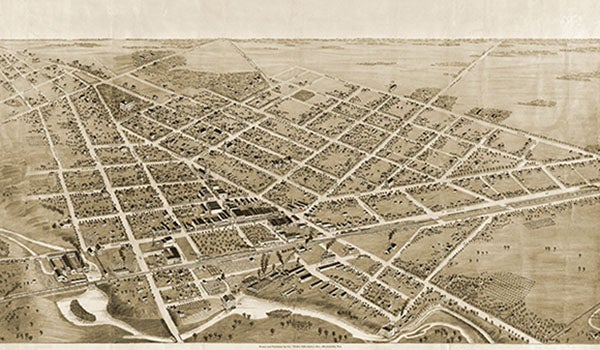

- 1890 Birds-Eye View shows the odd street grid of Dowagiac. The original plat ran parallel to the railroad tracks from Division St. to Chestnut (N-S) and Front Street to Indiana and Division (E-W) with later additions set up on a N-S-E-W grid. (Submitted)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

2023 marks the 175th anniversary of the founding of Dowagiac. To celebrate this milestone, Leader Publications – with help from the Dowagiac Area History Museum – will provide readers with a series of stories detailing the rich history of the Grand Old City. The stories will be released in digital on the third Friday of each month through the end of the year.

DOWAGIAC — The Grand Old City of Dowagiac is a treasure trove filled with more than 175 years of history.

The name Dowagiac comes from the Potawatomi Indian word, Ndowagayuk, which means “foraging ground”, reflective of this area’s abundant supply of wild game, fruit, vegetables, grain and medicinal herbs. In 1821, through the Treaty of Chicago, the Potawatomi, Chippewa and Ottawa ceded to the United States land today known as Cass County.

The Dowagiac Creek gave the city its start when its first known settler, William Renesten, established his carding mill in 1830. Two years later, he dammed the creek to create Mill Pond and built his grist mill. The mill was sold to Erastus Spaulding and later Horace Colby, becoming the Colby Mill, which served the city until 1948. Like Renesten, settlers wishing to live close to the mills, including Patrick Hamilton in 1835, the McComber family and Justus Gage, began to settle the area.

Waterpower supplied by Dowagiac Creek was important to early manufacturers. The creek furnished power for sawmills, a plug tobacco manufacturer, foundry, chair company, feed mill and a cider and vinegar producer.

A stagecoach route, following the Grand River Indian Trail, linking Kalamazoo to the Carey Mission in Niles, brought land seekers to the area by 1836.

“They would’ve come to a wooded area,” said Dowagiac Area History Museum Director Steve Arseneau. “They would’ve had to clear the woods and build themselves a log cabin for their families to reside and clear enough land to be able to farm the land – that’s what Patrick Hamilton was up to.”

According to Arseneau, excerpts from prominent Dowagiac settler Justus Gage detail the challenging conditions of frontier-era Dowagiac.

“It’s very swampy land, especially north of town,” Arseneau said. “He wrote about how when he was clearing the land, they started a fire. He said you could see swarms of mosquitoes going into the fire. It was like a wave of mosquitos swarming into the fire.”

In 1847, Nicholas Chesboro, a right of way buyer for the Michigan Central Railroad, Mitchel Robinson and Jacob Beeson, of Niles, bought a section of Patrick Hamilton’s 80 acres of land to establish a railroad station and route to New Buffalo.

“Initially, (the MCR) had a line to take it to where St. Joseph and Benton Harbor are today and down the lake shore to New Buffalo,” Arseneau said. “They decided a better route would take it through Cass County on a diagonal, which meant they had to purchase the right of way from people who already owned that land. Chesboro quickly recognized that Dowagiac would make a good spot for a depot because of proximity to the creek and steam engines needing water.”

On Feb. 16, 1848, the group registered the platt at the Cass County Historic Courthouse in Cassopolis and Dowagiac was born. The platt was incorporated as a village in 1863 and as a city in 1877.

Arseneau is unsure of how Chesboro and his team decided on the name Dowagiac for their settlement. While the Potawatomi had a presence in Southwest Michigan, Arseneau said there were no known settlements in the immediate area of the settlement.

“It’s always a bit of a mystery as to how they came up with that Dowagiac name,” he said. “Who was running into the Potawatomi where they would have heard that?”

When the Michigan Central Railroad came through in 1848, the area soon became a wheat shipping station. On wheat day, farmers waited in line for blocks to unload their grain. They also made use of the rail for shipping stock.

“The railroad changed everything,” Arseneau said. “For the people of the 19th century, the railroad was revolutionary. If you wanted to get from point A to B without the railroad, you were taking a wagon ride across poor roads and it would take you days to get across the state of Michigan. The railroad could cut down that trip and was a much smoother ride. For the industrial revolution, bringing in the raw materials for production and then taking away products as well. It was a vital part of building any community.”

Schoolhouses and churches were being established as early as the late 1830s. Arseneau said that one of the first schoolhouses only lasted one year due to complaints that the kids were picking up bad hits from their peers. Justus Gage, a Universalist pastor, raised $3,000 to build First Universalist Church of Dowagiac in 1859, which still stands today. According to Arseneau, at the time of completion, it was the town’s only auditorium. Black civil rights supporter Sojourner Truth and women’s rights advocate Susan B. Anthony were among the many famous individuals who used the church as a platform to spread their messages.

While town planners intended Main Street to be the principal street, merchants wanting to be near the railroad built their businesses along South Front Street. Fires in 1864 and 1866 destroyed the original downtown buildings before brick replacements were built that still stand proudly today.

“You had your shops – people setting up their general stores and creating the downtown district. You had your clergymen coming to town in the next couple of decades. Blacksmiths and mills were active and farmers were coming into town to purchase and sell goods. While the growth was small and incremental, those first couple decades really did see growth that established the foundation for the industrial revolution to come to Dowagiac with P.D. Beckwith.”

Next month: P.D. Beckwith, Round Oak and The Industrial Revolution