Historian describes horrors of American Civil War

Published 8:00 am Friday, September 8, 2017

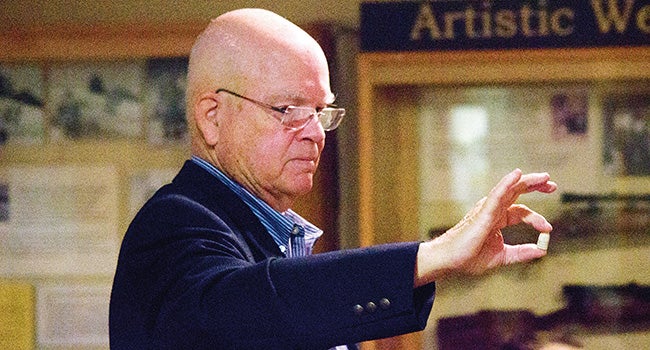

- (Leader photo/TED YOAKUM)

More than 150 years and dozens of armed conflicts later, the war between the boys in blue and the boys in grey remains the United States’ bloodiest conflict.

More than 600,000 Americans died fighting amongst each other during the four-year Civil War — a figure that is higher than the number of U.S. armed service personnel who perished in every other war the country has joined put together.

While the memory of the pain and bloodshed caused when brother faced brother on the battlefield has long since faded from the country’s collective conscious, historian Al McGeehan wants to remind citizens of what happens when Americans decide to resolve their political differences with bullets instead of debate, with bayonets instead of votes, with sabers instead of bills.

In light of the politically motived violence that erupted in Charlottesville and other communities across the country over the past year, McGeehan said everyone should take heed of the lessons of the American Civil War, something that “must not happen again.”

“I have talked about this subject for probably around 45 years,” the retired high school history teacher said during his remarks to audiences at the Dowagiac Area History Museum Wednesday. “Never has the subject been more ripe. Never has it been more real than it is in September 2017.”

McGeehan described the horrors of the Civil War during his presentation that evening at the local museum, in his talk “Honoring Michigan’s First Veterans: Michigan In the Civil War.” McGeehan, a longtime resident of Holland, Michigan, and an avid collector of Civil War artifacts, served as the first speaker of the history museum’s fall lecture series. His talk drew a packed house to the institution’s basement.

The speaker came to the museum with dozens of relics from the conflict in tow, which were on display behind him. Among the artifacts were several rifles, bullets and bayonets used by Union and Confederate soldiers during the war, as well as other items, including a battlefield surgeon’s kit, complete with a saw that doctors used to amputate infected limbs of the wounded.

In spite of the toll the conflict had on the country, when the first shots of the war between the North and South were exchanged at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, many citizens were excited about the prospect of war, which leaders expected to last no more than 90 days, McGeehan said.

Recruiting offices on both sides of country were flooded with men — and, in some rare instances, women who disguised themselves as the opposite sex in order to serve their country — wanting to enlist. Although both the Union and Confederacy forbade men under 18 from enlisting, many teenagers would place 18 cents worth of coins underneath their feet, so that when the recruiter made them swear they were “over 18,” the boys would not technically be lying when they answered “yes,” McGeehan said.

Those who did not volunteer to serve themselves treated the early days of the war as some kind of social gathering. During the first battle of Bull Run in July 1861, residents lined the outskirts of the battlefield to witness the engagement — some residents even baked pies or prepared picnic baskets to bring with them, McGeehan said.

At the end of the battle, nearly 5,000 soldiers died — only around 1,500 less than the number of troops who died in combat during the American Revolution.

“This certainly was no picnic,” McGeehan said. “It was no picnic at all. It was real war, and it was very up close, and very personal.”

During the opening months of the war, soldiers on both sides were largely disorganized. Troops wore whatever uniforms leaders could scrounge up, and were armed with rifles that were more than 30 years old.

However, as the conflict raged on, Union and Confederate leaders ordered millions of state-of-the-art firearms from Great Britain, France and Belgium. American inventors also crafted new weapons for troops to use, including the repeating rifle, which was used by members of the Michigan Calvary Brigade, led by General George Custer, to repel a sneak attack by Confederate forces in the famous Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, which helped lead the Union to victory that day.

“The southern boys didn’t know what hit them,” McGeehan said.

Away from the hell of the battlefield, soldiers waged war with disease and poor living conditions. Troops lived off coffee and hardtack, a biscuit made with flour, water and salt that, while long lasting, was hard as a brick and was often infested with maggots after spending months in storage.

“Of course, you had to have enough teeth [to eat it],” McGeehan said. “That’s why, to pass a physical at the beginning of the war, you had to demonstrate you had enough teeth — two on top, and two lowers — to tear the [bullet] cartridge and to eat the hardtack.”

After years of bloody combat, the Union prevailed over the Confederacy when Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House in Virginia on April 9, 1865.

During a victory celebration on the lawns of the White House shortly after the victory, the jubilant crowd asked President Abraham Lincoln to deliver a speech. The war weary leader declined their offer, and instead asked the band to play a song for him, telling them, “I always thought ‘Dixie’ was a nice song.”

“Throughout history, after civil wars, the losing side is annihilated,” McGeehan said. “You lose your land, you lose your property, you lose your life. After our Civil War, Lincoln simply wanted us to shake hands and become brothers once again.”

With the debate over the place of Confederate monuments in public spaces erupting over the last several weeks, McGeehan asked the audience to keep Lincoln’s wish for peace in mind.

“These monuments that were erected in the years following the ware were erected to demonstrate the healing that went on in American after this terrible, terrible episode,” he said. “That’s why they’re there.”