P.D. Beckwith and Round Oak’s growth

Published 11:34 am Monday, June 12, 2017

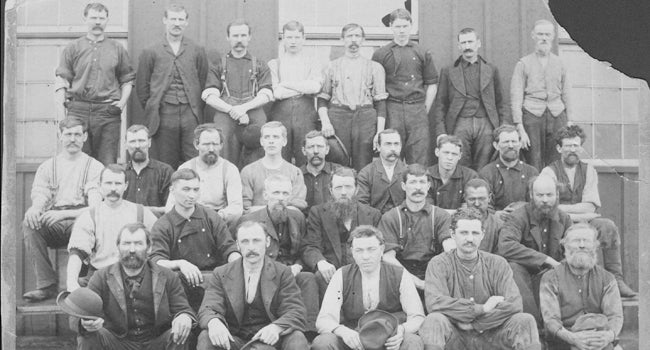

- P.D. Beckwith and part of the Round Oak Stove Company crew from the 1880s. (Submitted photo)

Last month, I looked at Philo D. Beckwith’s early years in Dowagiac.

While his manufacturing of the roller grain drill created a regular product, the drill was not enough to keep Beckwith profitable.

Because of his financial struggles, he cast himself a heating stove to heat the shop. It is said that Beckwith worked alongside his four employees in his foundry.

The stove was of rudimentary design, but it worked well and he continued to tinker with it to improve its efficiency. That initial stove would soon bring the Industrial Revolution to Dowagiac.

A representative from the Michigan Central Railroad Company visiting Beckwith at his foundry saw the stove and ordered one for the depot in Niles. Accepting old iron in exchange for stoves, Beckwith made the Niles depot stove and another for the Kalamazoo depot.

Soon, the Michigan Central ordered over 300 stoves for depots and other buildings along its line. P.D. Beckwith, after years of financial struggles, had finally hit upon a reliable product that proved popular.

In his first piece of marketing genius, Beckwith placed the first commercially available Round Oak stove in the barber shop of Thomas Jefferson Martin, a popular African-American barber in town. He likely reasoned that every man in town would eventually find their way into Martin’s shop and see the stove -— with the hope that some would buy a Round Oak.

An 1870 advertisement lists some of the customers who purchased stoves, and most are Cass County residents or businesses. There are a few customers listed from across the state of Michigan or the Chicago area.

Beckwith began applying for patents almost immediately and received several, including a few for design elements and others for modifications to heating features. Beckwith incorporated Round Oak in 1871 or 1872 (I have seen it listed both years by Round Oak) and the heating stove became his primary product, though he continued making the grain drill.

The stove business accelerated so quickly that one story is that Beckwith took his stove design to the Michigan Stove Company in Detroit to take over the manufacturing of it. They refused to take on the project, citing the simplicity of the stove’s design. Beckwith returned to Dowagiac, built up his factory and ramped up production.

I tell visitors to the museum that Round Oak succeeded for several reasons — the quality product that proved durable, good marketing materials and pricing the stove so most working class families could afford it.

The primary reason, however, is Philo D. Beckwith. He recognized that Round Oak’s success relied upon Dowagiac’s fortunes and vice-versa. He continually invested in both his company and the city.

He served as an alderman and mayor in the 1870s and 1880s, and was a noted philanthropist in town. Despite his success, he lived in a modest house on High Street — this allowed him to pour his profits into the Round Oak Stove Works and the city.

While P.D. Beckwith’s Round Oak Stove Works grew, he was also busy shaping his views about the world. In his era, he was called a ‘Free Thinker.’ Today, he might be called a progressive libertarian.

While he helped build some of the churches in the city, Beckwith does not appear to have been devoted to any particular religion. I believe he was likely an agnostic with the view that people were free to believe what they wanted without judgment from others. He became friends with the noted orator and Free Thinker Colonel Robert Ingersoll.

An article in the Cass County Republican on March 14, 1878, noted that Beckwith was elected to the executive committee of the “Liberal League of Dowagiac,” which encouraged “freethought on the subjects of civil, religious and political rights, and to encourage investigation in relations to science, religion and reform.”

The museum has one political manuscript written by P.D. Beckwith and it demonstrates that he did not think much of the U.S. system of government and its “polyticians,” who he felt had too much power.

Beckwith advocates for women’s suffrage as early as the 1880s and laments that “a minority of the people in general have elected our president through the unjust electoral college.”

As the 1870s move into the 1880s, Round Oak is beginning to influence Dowagiac and his stature would grow. Next month this column will look at this growing concern and Beckwith’s impact on the city.

Steve Arseneau is the director of the Dowagiac Area History Museum. He resides in Niles with his wife, Christina, and children, Theodore and Eleanor.